Dōgen

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

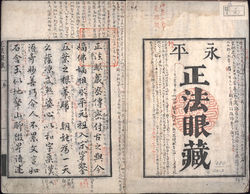

Dōgen Zenji (道元禅師; also Dōgen Kigen 道元希玄, or Eihei Dōgen 永平道元, or Koso Joyo Daishi) (19 January 1200 – 22 September 1253) was a Japanese Zen Buddhist teacher born in Kyōto, and the founder of the Sōtō school of Zen in Japan after travelling to China and training under the Chinese Caodong lineage there. Dōgen is known for his extensive writing including the Treasury of the Eye of the True Dharma or Shōbōgenzō, a collection of ninety-five fascicles concerning Buddhist practice and enlightenment.

Contents |

Biography

Early life

Dōgen probably was born into a noble family, though as an illegitimate child of Minamoto Michitomo, who served in the imperial court as a high-ranking ashō (亞相, "Councillor of State").[1]. His mother is said to have died when Dōgen was age 7.

Early training

At some later point, Dōgen became a low-ranking monk on Mount Hiei, the headquarters of the Tendai school of Buddhism. Later in life, while describing his time on Mt. Hiei, he writes that he became possessed by a single question with regard to the Tendai doctrine:

| “ | As I study both the exoteric and the esoteric schools of Buddhism, they maintain that human beings are endowed with Dharma-nature by birth. If this is the case, why did the Buddhas of all ages—undoubtedly in possession of enlightenment—find it necessary to seek enlightenment and engage in spiritual practice?[2] | ” |

This question was, in large part, prompted by the Tendai concept of "original enlightenment" (本覚 hongaku), which states that all human beings are enlightened by nature and that, consequently, any notion of achieving enlightenment through practice is fundamentally flawed[3].

As he found no answer to his question at Mount Hiei, and as he was disillusioned by the internal politics and need for social prominence for advancement,[1] Dōgen left to seek an answer from other Buddhist masters. Dōgen went to visit Kōin, the Tendai abbot of Onjōji Temple (園城寺), asking him this same question. Kōin said that, in order to find an answer, he might want to consider studying Chán in China[4]. In 1217, two years after the death of contemporary Zen Buddhist Myōan Eisai, Dōgen went to study at Kennin-ji Temple (建仁寺), under Eisai's successor, Myōzen (明全).[1] In 1223, Dōgen and Myōzen undertook the dangerous passage across the East China Sea to China to study in Jing-de-si (Ching-te-ssu, 景德寺) monastery as Eisai had once done.

Travel to China

In China, Dōgen first went to the leading Chan monasteries in Zhèjiāng province. At the time, most Chan teachers based their training around the use of gōng-àns (Japanese: kōan). Though Dōgen assiduously studied the kōans, he became disenchanted with the heavy emphasis laid upon them, and wondered why the sutras were not studied more. At one point, owing to this disenchantment, Dōgen even refused Dharma transmission from a teacher[5]. Then, in 1225, he decided to visit a master named Rújìng (如淨; J. Nyōjo), the thirteenth patriarch of the Cáodòng (J. Sōtō) lineage of Zen Buddhism, at Mount Tiāntóng (天童山 Tiāntóngshān; J. Tendōzan) in Níngbō. Rujing was reputed to have a style of Chan that was different from the other masters whom Dōgen had thus far encountered. In later writings, Dōgen referred to Rujing as "the Old Buddha". Additionally he affectionately described both Rujing and Myōzen as senshi (先師, "Former Teacher").[1]

Under Rujing, Dōgen realized liberation of body and mind upon hearing the master say, "Cast off body and mind" (身心脱落 shēn xīn tuō luò). This phrase would continue to have great importance to Dōgen throughout his life, and can be found scattered throughout his writings, as—for example—in a famous section of his "Genjōkōan" (現成公案):

| “ | To study the Way is to study the self. To study the self is to forget the self. To forget the self is to be enlightened by all things of the universe. To be enlightened by all things of the universe is to cast off the body and mind of the self as well as those of others. Even the traces of enlightenment are wiped out, and life with traceless enlightenment goes on forever and ever.[6] | ” |

Myōzen died shortly after Dōgen arrived at Mount Tiantong. In 1227[7], Dōgen received Dharma transmission and inka from Rujing, and remarked on how he had finally settled his "life's quest of the great matter"[8].

Return to Japan

Dōgen returned to Japan in 1227 or 1228, going back to stay at Kennin-ji, where he had trained previously.[9] [1]Among his first actions upon returning was to write down the Fukan Zazengi (普観坐禅儀; "Universally Recommended Instructions for Zazen"), a short text emphasizing the importance of and giving instructions for zazen, or sitting meditation. However, tension soon arose as the Tendai community began taking steps to suppress both Zen and Jōdo Shinshū, the new forms of Buddhism in Japan. In the face of this tension, Dōgen left the Tendai dominion of Kyōto in 1230, settling instead in an abandoned temple in what is today the city of Uji, south of Kyōto[10]. In 1233, Dōgen founded the Kannon-dōri-in[11] in Uji as a small center of practice; he later expanded this temple into the Kōshō-hōrinji Temple (興聖法林寺). In 1243, Hatano Yoshishige (波多野義重) offered to relocate Dōgen's community to Echizen province, far to the north of Kyōto. Dōgen accepted due to the ongoing tension with the Tendai community, and his followers built a comprehensive center of practice there, calling it Daibutsu Temple (大仏寺). While the construction work was going on, Dōgen would live and teach at Yoshimine-dera Temple (Kippōji, 吉峯寺), which is located close to Daibutsuji. In 1246, Dōgen renamed Daibutsuji, calling it Eihei-ji. This temple remains one of the two head temples of Sōtō Zen in Japan today, the other being Sōji-ji.

Dōgen spent the remainder of his life teaching and writing at Eiheiji. In 1247, the newly installed shōgun's regent, Hōjō Tokiyori, invited Dōgen to come to Kamakura to teach him. Dōgen made the rather long journey east to provide the shōgun with lay ordination, and then returned to Eiheiji in 1248. In the autumn of 1252, Dōgen fell ill, and soon showed no signs of recovering. He presented his robes to his main apprentice, Koun Ejō (孤雲懐弉), making him the abbot of Eiheiji. Then, at Hatano Yoshishige's invitation, Dōgen left for Kyōto in search of a remedy for his illness. In 1253, soon after arriving in Kyōto, Dōgen died. Shortly before his death, he had written a death poem:

- Fifty-four years lighting up the sky.

- A quivering leap smashes a billion worlds.

- Hah!

- Entire body looks for nothing.

- Living, I plunge into Yellow Springs.[12]

Dōgen's Zen

At the heart of the variety of Zen that Dōgen taught are a number of key concepts, which are emphasized repeatedly in his writings. All of these concepts, however, are closely interrelated to one another insofar as they are all directly connected to zazen, or sitting meditation, which Dōgen considered to be identical to Zen, as is pointed out clearly in the first sentence of the 1243 instruction manual "Zazen-gi" (坐禪儀; "Principles of Zazen"): "Studying Zen ... is zazen"[13]. In referring to zazen, Dōgen is most often referring specifically to shikantaza, roughly translatable as "nothing but precisely sitting", which is a kind of sitting meditation in which the meditator sits "in a state of brightly alert attention that is free of thoughts, directed to no object, and attached to no particular content"[14].

Oneness of practice-enlightenment

The primary concept underlying Dōgen's Zen practice is "oneness of practice-enlightenment" (修證一如 shushō-ittō / shushō-ichinyo). In fact, this concept is considered so fundamental to Dōgen's variety of Zen—and, consequently, to the Sōtō school as a whole—that it formed the basis for the work Shushō-gi (修證儀), which was compiled in 1890 by Takiya Takushū (滝谷卓洲) of Eihei-ji and Azegami Baisen (畔上楳仙) of Sōji-ji as an introductory and prescriptive abstract of Dōgen's massive work, the Shōbōgenzō ("Treasury of the Eye of the True Dharma").

For Dōgen, the practice of zazen and the experience of enlightenment were one and the same. This point was succinctly stressed by Dōgen in the Fukan Zazengi, the first text that he composed upon his return to Japan from China: "To practice the Way singleheartedly is, in itself, enlightenment. There is no gap between practice and enlightenment or zazen and daily life"[15]. Earlier in the same text, the basis of this identity is explained in more detail:

| “ | Zazen is not "step-by-step meditation". Rather it is simply the easy and pleasant practice of a Buddha, the realization of the Buddha's Wisdom. The Truth appears, there being no delusion. If you understand this, you are completely free, like a dragon that has obtained water or a tiger that reclines on a mountain. The supreme Law will then appear of itself, and you will be free of weariness and confusion.[16] | ” |

The "oneness of practice-enlightenment" was also a point stressed in the Bendōwa (弁道話 "A Talk on the Endeavor of the Path") of 1231:

| “ | Thinking that practice and enlightenment are not one is no more than a view that is outside the Way. In buddha-dharma [i.e. Buddhism], practice and enlightenment are one and the same. Because it is the practice of enlightenment, a beginner's wholehearted practice of the Way is exactly the totality of original enlightenment. For this reason, in conveying the essential attitude for practice, it is taught not to wait for enlightenment outside practice.[17] | ” |

Writings

Dōgen's masterpiece is the aforementioned Shōbōgenzō, talks and writings—collected together in ninety-five fascicles—on topics ranging from monastic practice to the philosophy of language, being, and time. In the work, as in his own life, Dōgen emphasized the absolute primacy of shikantaza and the inseparability of practice and enlightenment.

Dōgen also compiled a collection of 301 koans in Chinese without commentaries added. Often called the Shinji Shōbōgenzō (shinji:”original or true characters” and shōbōgenzō, variously translated as “the right-dharma-eye treasury” or “Treasury of the Eye of the True Dharma” ). The collection is also known as the Shōbōgenzō Sanbyakusoku (The Three Hundred Verse Shōbōgenzō”) and the Mana Shōbōgenzō, where mana is an alternative reading of shinji. The exact date the book was written is in dispute but Nishijima believes that Dogen may well have begun compiling the koan collection before his trip to China. [18] Although these stories are commonly referred to as kōans, Dōgen referred to them as kosoku (ancestral criteria) or innen (circumstances and causes or results, of a story). The word kōan for Dogen meant “absolute reality” or the “universal Dharma”. [19]

Lectures that Dōgen gave to his monks at his monastery, Eihei-ji, were compiled under the title Eihei Kōroku, also known as Dōgen Oshō Kōroku (The Extensive Record of Teacher Dōgen’s Sayings) in ten volumes. The sermons, lectures, sayings and poetry were compiled shortly after Dōgen’s death by his main disciples, Koun Ejō (孤雲懐奘, 1198-1280) , Senne and Gien. There are three different editions of this text: the Rinnōji text from 1598; a popular version printed in 1672 and a version discovered at Ehei-ji in 1937 which, although undated, is believed to be the oldest extant version. [20] Another collection of his talks is the Shōbōgenzō Zuimonki (Gleanings from Master Dōgen’s Sayings) in six volumes. These are talks that Dōgen gave to his leading disciple, Ejō, who became Dōgen’s disciple in 1234. The talks were recorded and edited by Ejō.

The earliest work by Dōgen is the Hōkojōki (Memoirs of the Hōkyō Period). This one volume work is a collection of questions and answers between Dōgen and his Chinese teacher, Tiāntóng Rújìng (天童如淨; Japanese: Tendō Nyōjo, 1162-1228). The work was discovered among Dōgen’s papers by Ejō in 1253, just three months after Dōgen’s death.

Other notable writings of Dōgen are:

-

- Fukan-zazengi (General Advice on the Principles of Zazen), one volume; probably written immediately after Dōgen’s return from China in 1227

- Eihei shoso gakudō-yōinshū (Advice on Studying the Way), one volume; probably written in 1234

- Tenzo-kyōkun (Instructions to the Chief Cook), one volume; written in 1237

- Benōhō (Rules for the Practice of the Way), one volume; written between 1244 and 1246 [21]

While it was customary for Buddhist works to be written in Chinese, Dōgen often wrote in Japanese, conveying the essence of his thought in a style that was at once concise, compelling, and inspiring. A master stylist, Dōgen is noted not only for his prose, but also for his poetry (in Japanese waka style and various Chinese styles). Dōgen's use of language is unconventional by any measure. According to Dōgen scholar Steven Heine: "Dogen's poetic and philosophical works are characterized by a continual effort to express the inexpressible by perfecting imperfectable speech through the creative use of wordplay, neologism, and lyricism, as well as the recasting of traditional expressions"[22].

Legacy

Dōgen's teachings were transmitted by his immediate pupils, including:

- Koun Ejō, commentator on the Shobogenzo, and former Darumashū elder

- Giin, through Ejō

- Gikai, through Ejō

- Gien, through Ejō

- Jakuen, the only Chinese disciple in the original community

- Sōkai

- Senne, another commentator of the Shobogenzo.

But his most notable successor was Keizan (瑩山; 1268–1325), founder of Sōjiji Temple and author of the Record of the Transmission of Light (傳光錄 Denkōroku), which traces the succession of Zen masters from Siddhārtha Gautama up to Keizan's own day. Together, Dōgen and Keizan are regarded as the founders of the Sōtō school in Japan.

| Buddhist titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Rujing |

Sōtō Zen patriarch 1227–1253 |

Succeeded by Koun Ejo |

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Bodiford, William M. (2008). Soto Zen in Medieval Japan (Studies in East Asian Buddhism). University of Hawaii Press. pp. 22–36. ISBN 0824833031.

- ↑ Ibid. 22

- ↑ Abe 19–20

- ↑ Tanahashi 4

- ↑ Ibid. 5

- ↑ Kim 125

- ↑ Tanahashi 6

- ↑ Ibid. 144

- ↑ Ibid. 6

- ↑ Ibid. 39

- ↑ Ibid. 7

- ↑ Qtd. in Tanahashi, 219

- ↑ "Principles of Zazen"; tr. Bielefeldt, Carl.

- ↑ Kohn 196–197

- ↑ Yukoi 47

- ↑ Ibid. 46

- ↑ Okumura 30

- ↑ Nishijima, 2003:i

- ↑ Yasutani, 1996:8

- ↑ Kim, 1987:236-7

- ↑ see Kim, 1987, Appendix B pp234-237 for a more complete list of Dōgen’s major writings

- ↑ Heine 1997, 67

References

- Abe, Masao. A Study of Dōgen: His Philosophy and Religion. Ed. Heine, Steven. Albany: SUNY Press, 1992. ISBN 0-7914-0838-8.

- Cleary, Thomas. Rational Zen: The Mind of Dogen Zenji. Boston: Shambhala Publications, Inc., 1992. ISBN 0-87773-973-0.

- Dogen. The Heart of Dogen's Shobogenzo. Tr. Waddell, Norman and Abe, Masao. Albany: SUNY Press, 2002. ISBN 0-7914-5242-5.

- Heine, Steven. Dogen and the Koan Tradition: A Tale of Two Shobogenzo Texts. Albany: SUNY Press, 1994. ISBN 0-7914-1773-5.

- —. The Zen Poetry of Dogen: Verses from the Mountain of Eternal Peace. Boston: Tuttle Publishing, 1997. ISBN 0-8048-3107-6.

- Kim, Hee-jin. Eihei Dogen, Mystical Realist. Wisdom Publications, (1975, 1980, 1987) 2004. ISBN 0-86171-376-1.

- Kohn, Michael H.; tr. The Shambhala Dictionary of Buddhism and Zen. Boston: Shambhala Publications, Inc., 1991. ISBN 0-87773-520-4.

- LaFleur, William R.; ed. Dogen Studies. The Kuroda Institute, 1985. ISBN 0-8248-1011-2.

- Masunaga, Reiho. A Primer of Soto Zen. University of Hawaii: East-West Center Press, 1978. ISBN 0-7100-8919-8.

- Okumura, Shohaku; Leighton, Taigen Daniel; et al.; tr. The Wholehearted Way: A Translation of Eihei Dogen's Bendowa with Commentary. Boston: Tuttle Publishing, 1997. ISBN 0-8048-3105-X.

- Nishijima, Gudo, Master Dōgen's Shinji Shobogenzo, 301 Koan Stories. Ed. M. Luetchford, J. Peasons. Windbell. 2003

- Nishijima, Gudo & Cross, Chodo; tr. 'Master Dogen's Shobogenzo' in 4 volumes. Windbell Publications, 1994. ISBN 0-9523002-1-4

- Tanahashi, Kazuaki; ed. Moon In a Dewdrop: Writings of Zen Master Dogen. New York: North Point Press, 1997. ISBN 0-86547-186-X.

- Tanahashi, Kazuaki (tr.) & Loori, Daido (comm.) : The True Dharma Eye. Shambhala, Boston, 2005.

- Yokoi, Yūhō and Victoria, Daizen; tr. ed. Zen Master Dōgen: An Introduction with Selected Writings. New York: Weatherhill Inc., 1990. ISBN 0-8348-0116-7.

- Yasutani, Hakuun; Flowers Fall: A Commentary on Zen Master Dōgen's Genjokoan. Boston: Shambhala Publications, 1996. ISBN 1-57062-103-9

External links

- Who is Dogen Zenji? Message from Dogen

- Dogen Translations Translations of Dogen and other works by Anzan Hoshin.

- Genjo Koan, Uji, Bendowa, and Soshi Seirai I, texts written by Dogen (annotated English translations)

- Translations of the Shobogenzo incomplete, an ongoing project by the Soto Zen Text Project

- Understanding the Shobogenzo by Gudo Nishijima

- Instructions for the cook

- Dogen and Koans by John Daido Loori

- Shusho-gi, Online Translation by Neil Christopher

- Gakudo Yojin-shu, Online Translation by Neil Christopher

- Shushogi What is Truly Meant by Training and Enlightenment

- The Complete Shobogenzo free for download

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||